I recently came across this question on Cross Validated, and I thought it offered a great opportunity to use R and ggplot2 to explore, in depth, the assumptions underlying the k-means algorithm. The question, and my response, follow.

K-means is a widely used method in cluster analysis. In my understanding, this method does NOT require ANY assumptions, i.e., give me a data set and a pre-specified number of clusters, k, then I just apply this algorithm which minimize the SSE, the within cluster square error.

So k-means, it is essentially an optimization problem.

I read some material about the drawback of k-means, most of them says that:

k-means assume the variance of the distribution of each attribute (variable) is spherical;

all variables have the same variance;

the prior probability for all k clusters are the same, i.e. each cluster has roughly equal number of observations; If any one of these 3 assumptions is violated, then k-means will fail.

I could not understand the logic behind this statement. I think k-means method essentially makes no assumptions, it just minimizes the SSE, I cannot see the link between minimizing the SSE and those 3 “assumptions”.

What a great question- it’s a chance to show how one would inspect the drawbacks and assumptions of any statistical method. Namely: make up some data and try the algorithm on it!

We’ll consider two of your assumptions, and we’ll see what happens to the k-means algorithm when those assumptions are broken. We’ll stick to 2-dimensional data since it’s easy to visualize. (Thanks to the curse of dimensionality, adding additional dimensions is likely to make these problems more severe, not less). We’ll work with the statistical programming language R: you can find the full code here.

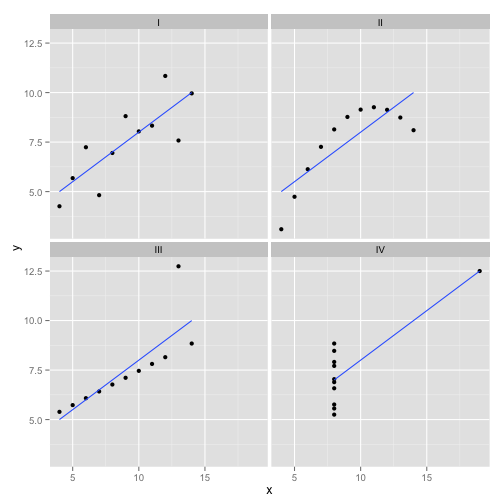

Diversion: Anscombe’s Quartet

First, an analogy. Imagine someone argued the following:

I read some material about the drawbacks of linear regression- that it expects a linear trend, that the residuals are normally distributed, and that there are no outliers. But all linear regression is doing is minimizing the sum of squared errors (SSE) from the predicted line. That’s an optimization problem that can be solved no matter what the shape of the curve or the distribution of the residuals is. Thus, linear regression requires no assumptions to work.

Well, yes, linear regression works by minimizing the sum of squared residuals. But that by itself is not the goal of a regression: what we’re trying to do is draw a line that serves as a reliable, unbiased predictor of y based on x. The Gauss-Markov theorem tells us that minimizing the SSE accomplishes that goal- but that theorem rests on some very specific assumptions. If those assumptions are broken, you can still minimize the SSE, but it might not do anything. Imagine saying “You drive a car by pushing the pedal. The pedal can be pushed no matter how much gas in the tank. Therefore, even if the tank is empty, you can still push the pedal and drive the car.”

But talk is cheap. Let’s look at the cold, hard, data. Or actually, made-up data.

This is my favorite made-up data: Anscombe’s Quartet. Created in 1973 by statistician Francis Anscombe, this delightful concoction illustrates the folly of trusting statistical methods blindly. Each of the datasets has the same linear regression slope, intercept, p-value and $R^2$- and yet at a glance we can see that only one of them, I, is appropriate for linear regression. In II it suggests the wrong shape, in III it is skewed by a single outlier- and in IV there is clearly no trend at all!

One could say “Linear regression is still working in those cases, because it’s minimizing the sum of squares of the residuals.” But what a Pyrrhic victory! Linear regression will always draw a line, but if it’s a meaningless line, who cares?

So now we see that just because an optimization can be performed doesn’t mean we’re accomplishing our goal. And we see that making up data, and visualizing it, is a good way to inspect the assumptions of a model. Hang on to that intuition, we’re going to need it in a minute.

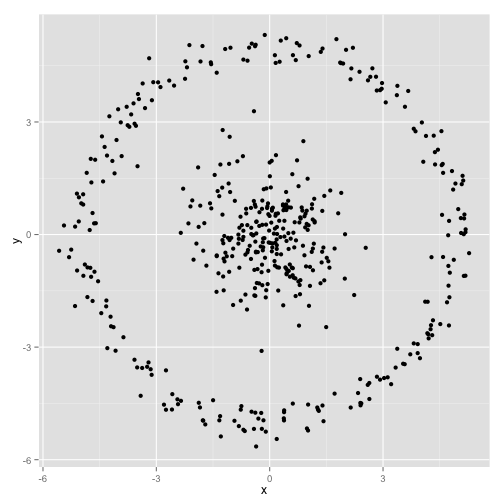

Broken Assumption: Non-Spherical Data

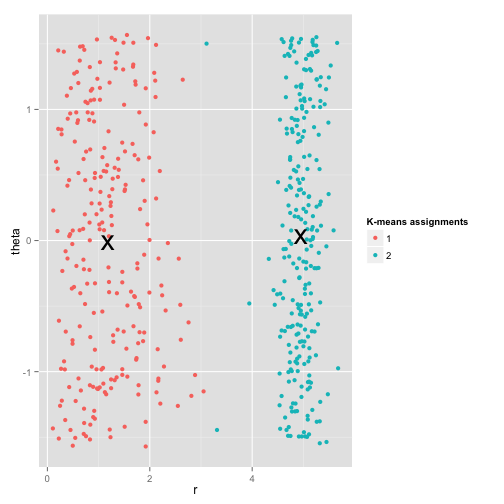

You argue that the k-means algorithm will work fine on non-spherical clusters. Non-spherical clusters like… these?

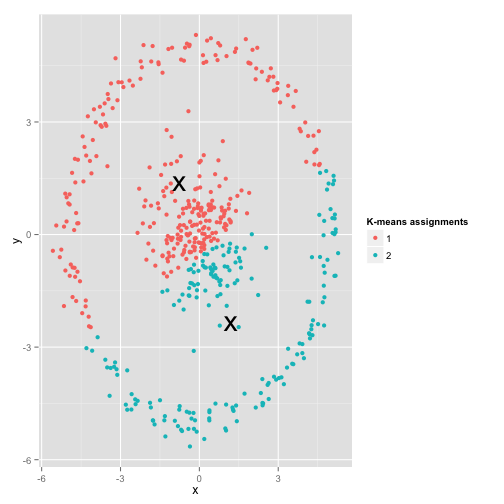

Maybe this isn’t what you were expecting- but it’s a perfectly reasonable way to construct clusters. Looking at this image, we humans immediately recognize two natural groups of points- there’s no mistaking them. So let’s see how k-means does: assignments are shown in color, imputed centers are shown as X’s.

Well, that’s not right. K-means was trying to fit a square peg in a round hole- trying to find nice centers with neat spheres around them- and it failed. Yes, it’s still minimizing the within-cluster sum of squares- but just like in Anscombe’s Quartet above, it’s a Pyrrhic victory!

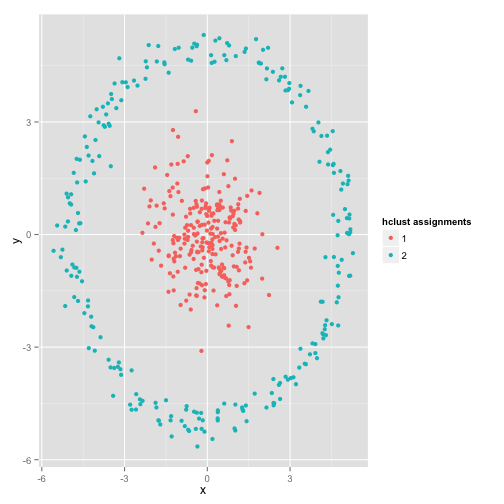

You might say “That’s not a fair example… no clustering method could correctly find clusters that are that weird.” Not true! Try single linkage hierachical clustering:

Nailed it! This is because single-linkage hierarchical clustering makes the right assumptions for this dataset. (There’s a whole other class of situations where it fails).

You might say “That’s a single, extreme, pathological case.” But it’s not! For instance, you can make the outer group a semi-circle instead of a circle, and you’ll see k-means still does terribly (and hierarchical clustering still does well). I could come up with other problematic situations easily, and that’s just in two dimensions. When you’re clustering 16-dimensional data, there’s all kinds of pathologies that could arise.

Lastly, I should note that k-means is still salvagable! If you start by transforming your data into polar coordinates, the clustering now works:

That’s why understanding the assumptions underlying a method is essential: it doesn’t just tell you when a method has drawbacks, it tells you how to fix them.

Unevenly sized clusters

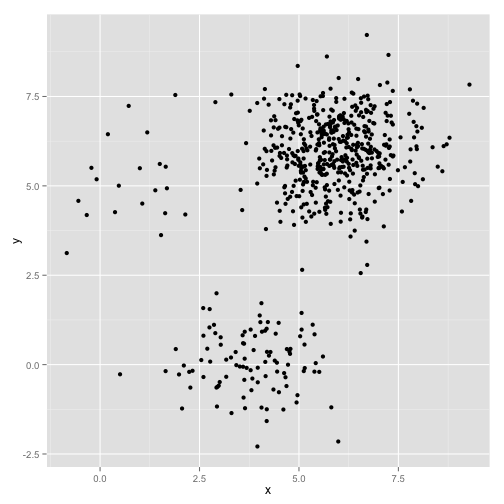

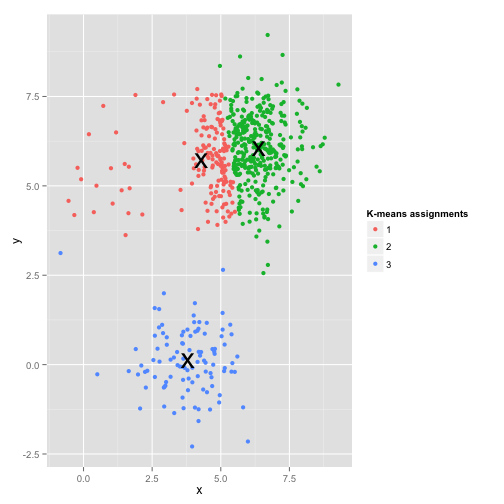

What if the clusters have an uneven number of points- does that also break k-means clustering? Well, consider this set of clusters, of sizes 20, 100, 500. I’ve generated each from a multivariate Gaussian:

This looks like k-means could probably find those clusters, right? Everything seems to be generated into neat and tidy groups. So let’s try k-means:

Ouch. What happened here is a bit subtler. In its quest to minimize the within-cluster sum of squares, the k-means algorithm gives more “weight” to larger clusters. In practice, that means it’s happy to let that small cluster end up far away from any center, while it uses those centers to “split up” a much larger cluster.

If you play with these examples a little (R code here!), you’ll see that you can construct far more scenarios where k-means gets it embarrassingly wrong.

Conclusion: No Free Lunch

There’s a charming construction in mathematical folklore, formalized by Wolpert and Macready, called the “No Free Lunch Theorem.” It’s probably my favorite theorem in machine learning philosophy, and I relish any chance to bring it up (did I mention I love this question?) The basic idea is stated (non-rigorously) as this: “When averaged across all possible situations, every algorithm performs equally well.”

Sound counterintuitive? Consider that for every case where an algorithm works, I could construct a situation where it fails terribly. Linear regression assumes your data falls along a line- but what if it follows a sinusoidal wave? A t-test assumes each sample comes from a normal distribution: what if you throw in an outlier? Any gradient ascent algorithm can get trapped in local maxima, and any supervised classification can be tricked into overfitting.

What does this mean? It means that assumptions are where your power comes from! When Netflix recommends movies to you, it’s assuming that if you like one movie, you’ll like similar ones (and vice versa). Imagine a world where that wasn’t true, and your tastes are perfectly random- scattered haphazardly across genres, actors and directors. Their recommendation algorithm would fail terribly. Would it make sense to say “Well, it’s still minimizing some expected squared error, so the algorithm is still working”? You can’t make a recommendation algorithm without making some assumptions about users’ tastes- just like you can’t make a clustering algorithm without making some assumptions about the nature of those clusters.

So don’t just accept these drawbacks. Know them, so they can inform your choice of algorithms. Understand them, so you can tweak your algorithm and transform your data to solve them. And love them, because if your model could never be wrong, that means it will never be right.