A family member recently sent me a puzzle:

One hundred people are lined up with their boarding passes showing their seats on the 100-seat Plane. The first guy in line drops his pass as he enters the plane, and unable to pick it up with others behind him sits in a random seat. The people behind him, who have their passes, sit in their seats until one of them comes upon someone sitting in his seat, and takes his seat in a new randomly chosen seat. This process continues until there is only one seat left for the last person.

What is the probability that the last person will sit in the correct seat?

This took me a little time to work out mathematically (if you want some good solutions and explanations, see here). But I became interested in solving the problem using a Monte Carlo simulation.

R is excellent at solving many kinds of probability puzzles through simulation, often with concise and efficient approaches. For a puzzle like “What are the chances three people on an elevator with 13 buttons press three consecutive floors”, an R simulation can easily fit in a tweet:

mean(replicate(1e5, all(diff(sort(sample(13, 3, TRUE))) == 1)))## [1] 0.02951But it’s not immediately obvious how to simulate the boarding pass puzzle in R. This is because there’s a relationship between each passenger’s options and the choices of previous passengers. This means we have to keep track of state across steps, which makes it difficult to use our usual vectorization tricks. If we’re not careful, we might start building loops within loops and building up objects incrementally, approaches which are very slow in R.

Here I’ll show how to approach a puzzle like this while still taking advantage of R vectorization. Though I’ll walk through the code, this is not an introductory lesson; it’s intended for people who have some familiarity with the language.

Simulation code

A typical Monte Carlo simulation won’t simulate a single instance of loading the plane, because we can’t make any conclusions from that. We might perform 100,00 simulations of the plane, and examine the frequency of particular outcomes: how many times did the 100th passenger sit in the 100th seat?

The main trick for performing this simulation efficiently in R is that we’re not going to think “how would I simulate a single plane,” and then repeat it. That’s inefficient, since R adds some overhead for each operation that would add up quickly (see the Appendix below for a speed comparison with a single-plane approach). Instead, we perform the simulation across all 100,000 planes at the same time.

Here’s my approach to that:

simulate_seats <- function(seats = 100, planes = 100000) {

m <- matrix(seq_len(seats), nrow = seats, ncol = planes)

m[1, ] <- sample(seats, planes, replace = TRUE)

m[cbind(m[1, ], seq_len(planes))] <- 1

for (i in seq(2, seats - 1)) {

taken <- which(m[i, ] != i)

switch_with <- sample(seq(i, seats), length(taken), replace = TRUE)

replacements <- m[cbind(switch_with, taken)]

m[cbind(switch_with, taken)] <- m[i, taken]

m[i, taken] <- replacements

}

m

}There’s a lot going on in that function, so let’s walk through step-by-step with a smaller number of seats and planes.

set.seed(2015)

seats <- 10

planes <- 5

m <- matrix(seq_len(seats), nrow = seats, ncol = planes)

m## [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4] [,5]

## [1,] 1 1 1 1 1

## [2,] 2 2 2 2 2

## [3,] 3 3 3 3 3

## [4,] 4 4 4 4 4

## [5,] 5 5 5 5 5

## [6,] 6 6 6 6 6

## [7,] 7 7 7 7 7

## [8,] 8 8 8 8 8

## [9,] 9 9 9 9 9

## [10,] 10 10 10 10 10This is a simulation where each row represents a person’s seat, and each column is a separate instance of the simulation (10 seats on each of 5 planes). Right now, everyone is sitting in their proper seat. If that happens, there’s no puzzle. Let’s put the first person in a random seat, in every single plane.

# first row is the first seat

m[1, ] <- sample(seats, planes, replace = TRUE)

m## [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4] [,5]

## [1,] 1 9 3 1 2

## [2,] 2 2 2 2 2

## [3,] 3 3 3 3 3

## [4,] 4 4 4 4 4

## [5,] 5 5 5 5 5

## [6,] 6 6 6 6 6

## [7,] 7 7 7 7 7

## [8,] 8 8 8 8 8

## [9,] 9 9 9 9 9

## [10,] 10 10 10 10 10Now, that means that a later person isn’t able to get that seat. Let’s give each of those later people seat 1 for now. (Don’t worry: we know they may not actually stay in seat 1).

m[cbind(m[1, ], seq_len(planes))] <- 1

m## [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4] [,5]

## [1,] 1 9 3 1 2

## [2,] 2 2 2 2 1

## [3,] 3 3 1 3 3

## [4,] 4 4 4 4 4

## [5,] 5 5 5 5 5

## [6,] 6 6 6 6 6

## [7,] 7 7 7 7 7

## [8,] 8 8 8 8 8

## [9,] 9 1 9 9 9

## [10,] 10 10 10 10 10(That cbind trick is a neat way to assign to multiple values in different rows and columns of a matrix: see this section of Advanced R for more).

Now we’ll need to walk through each of the additional seats, except the last person. In each case:

- If the person is still assigned to their own seat, we don’t need to do anything.

- Otherwise, have them randomly choose to switch with someone who hasn’t sat down yet.

for (i in seq(2, seats - 1)) {

# only take someone's seat if this is not the right one. Leave others as is

taken <- which(m[i, ] != i)

# For those that are taken, switch with someone left (maybe themselves)

# that means somebody between [i, seats], inclusive

switch_with <- sample(seq(i, seats), length(taken), replace = TRUE)

# switch those chosen people's seats with these people's seats

replacements <- m[cbind(switch_with, taken)]

m[cbind(switch_with, taken)] <- m[i, taken]

m[i, taken] <- replacements

}This leaves us with the matrix:

m## [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4] [,5]

## [1,] 1 9 3 1 2

## [2,] 2 2 2 2 5

## [3,] 3 3 6 3 3

## [4,] 4 4 4 4 4

## [5,] 5 5 5 5 1

## [6,] 6 6 9 6 6

## [7,] 7 7 7 7 7

## [8,] 8 8 8 8 8

## [9,] 9 10 10 9 9

## [10,] 10 1 1 10 10In this case, 3 out of 5 simulated planes had the 10th passenger in the 10th seat.

Simulation results

Now we actually want to get an answer rather than check our math. We’ll simulate 100,000 planes, each with 100 seats:

set.seed(2015)

sim <- simulate_seats(seats = 100, planes = 100000)The probability of the final (100th) person sitting in the correct seat is:

mean(sim[100, ] == 100)## [1] 0.49562That is, 49.6%. Our simulation got close to the correct answer (spoiler alert!) of 50%.

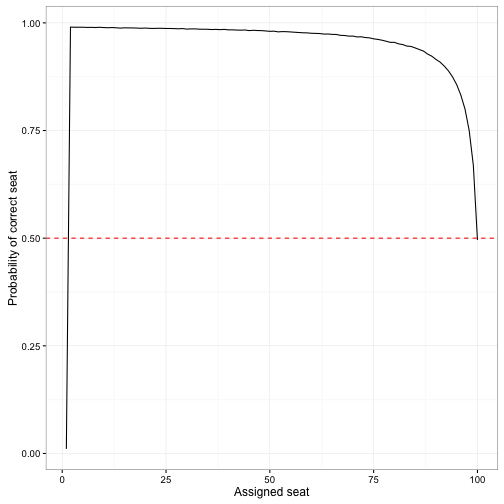

We can also look at the probability of sitting in the correct seat as a function of the person’s assigned seat.

correct_by_seat <- rowMeans(sim == seq_len(100))

library(ggplot2)

theme_set(theme_bw())

qplot(seq_along(correct_by_seat), correct_by_seat, geom = "line",

xlab = "Assigned seat",

ylab = "Probability of correct seat") +

geom_hline(yintercept = .5, color = "red", lty = 2)

Here we see that the first person has (as we’d expect) a 1/100 chance of sitting in the right seat. Then that after that people are increasingly unlikely to end up in their seat, until it reaches 50% for the last person.

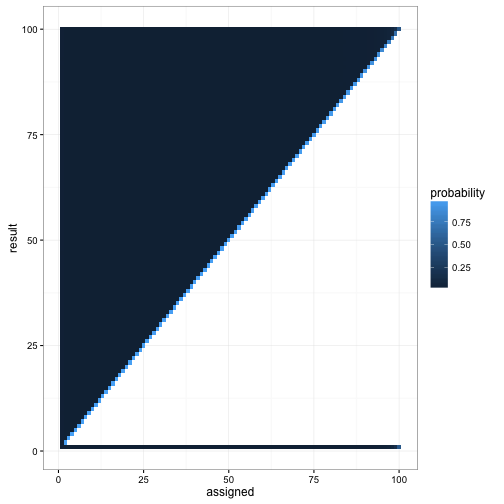

You may have noticed in our walkthrough earlier that in all the cases where passenger 100 does not sit in his own seat, he ends up sitting in passenger 1’s seat. What other patterns might appear in terms of who gets shuffled where? We can find out with a bit of dplyr/reshape2 manipulation:

library(reshape2)

library(dplyr)

probabilities <- sim %>%

melt(varnames = c("assigned", "simulation"), value.name = "result") %>%

count(assigned, result) %>%

mutate(probability = n / sum(n))

ggplot(probabilities, aes(assigned, result, fill = probability)) +

geom_tile() +

theme_bw()

Here we see that no one ever ends up in an earlier passenger’s seat, except for passenger 1’s seat. (This makes sense: if an earlier passenger’s seat were available, that passsenger would have taken it!) This confirms that our simulation worked how we expected it to.

This is an advantage to working with the “all simulations in a matrix” approach; we keep all the intermediate results. This is also an advantage to working in R as opposed to, say, C or C++: once you’ve performed your simulations, you have great tools for summarizing and visualizing those results.

Lessons

What lessons can we take from this simulation?

-

Sometimes, it’s good to use a for loop. This section of Advanced R reviews some of the situations where you need to use a loop. In particular, here there is a recursive relationship (not to be confused with a recursive function) between each passenger’s options and where the previous passengers had sit.

-

If you can’t vectorize across steps within your simulation, vectorize across simulation replications. We had a for loop across passengers boarding the plane: that was unavoidable. But we didn’t have a loop for each plane. This let us take advantage of vectorization in cases where we were performing the same operation in all of our simulations.

-

Never build up data structures incrementally. Notice that I started the simulation by allocating the

matrix(seq_len(seats), nrow = seats, ncol = planes)matrix. Building this up withrbindcalls would have been disastrous. (See the Modification in place section of Advanced R for more!) -

When working with matrices/arrays, know your subsetting operations well. When used right, these can be among the highest performance operations in R.

Challenge

So that’s my fastest approach to this simulation. Can you beat it?

- In R? Am I missing some vectorization trick? I’ve found a few optimizations that shave off about 1-2% of the running time, but generally at the expense of readability so they’re not really worth including. (Using Rcpp to beat me doesn’t count, but you can use other third-party packages).

- Using other statistical programming languages? I’m sure this problem can be solved faster in C or C++, but I’m interested in seeing how efficient solutions in Python, MATLAB and Julia compare.

If you come up with faster simulations, please share!

Appendix: Simulations on each individual plane

You might be wondering whether this approach of working across all planes simulataneously is really worth the trouble. Well, here’s an alternative approach, where the simulate_plane function simulates a single plane.

simulate_plane <- function(seats) {

v <- seq_len(seats)

# first person gets a random seat, switches with someone remaining

v[1] <- sample(seats, 1)

v[v[1]] <- 1

for (i in seq(2, seats - 1)) {

# if your seat isn't available, switch seats with someone remaining

if (v[i] != i) {

switch_with <- sample(seq(i, seats), 1)

v[c(i, switch_with)] <- v[c(switch_with, i)]

}

}

v

}Notice that this function is almost precisely analogous to the above simulate_seats function, except it is operating on a vector rather than a matrix. We can compare the performance of one-plane-at-a-time simulation to our all-at-once approach:

library(microbenchmark)

microbenchmark(simulate_seats(100, 1000),

replicate(1000, simulate_plane(100)))## Unit: milliseconds

## expr min lq mean

## simulate_seats(100, 1000) 5.007697 5.255132 5.698274

## replicate(1000, simulate_plane(100)) 115.776658 119.903931 126.040984

## median uq max neval cld

## 5.402015 5.91426 10.58789 100 a

## 121.936484 123.74800 426.96380 100 bWe notice that we get about a 20x speed improvement using the matrix approach.